Option (finance)

In finance, an option is a derivative financial instrument that specifies a contract between two parties for a future transaction on an asset at a reference price.[1] The buyer of the option gains the right, but not the obligation, to engage in that transaction, while the seller incurs the corresponding obligation to fulfil the transaction. The price of an option derives from the difference between the reference price and the value of the underlying asset (commonly a stock, a bond, a currency or a futures contract) plus a premium based on the time remaining until the expiration of the option. Other types of options exist, and options can in principle be created for any type of valuable asset.

An option which conveys the right to buy something at a specific price is called a call; an option which conveys the right to sell something at a specific price is called a put. The reference price at which the underlying asset may be traded is called the strike price or exercise price. The process of activating an option and thereby trading the underlying at the agreed-upon price is referred to as exercising it. Most options have an expiration date. If the option is not exercised by the expiration date, it becomes void and worthless.[1]

In return for assuming the obligation, called writing the option, the originator of the option collects a payment, the premium, from the buyer. The writer of an option must make good on delivering (or receiving) the underlying asset or its cash equivalent, if the option is exercised.

An option can usually be sold by its original buyer to another party. Many options are created in standardized form and traded on an anonymous options exchange among the general public, while other over-the-counter options are customized ad hoc to the desires of the buyer, usually by an investment bank.[2][3]

Contents |

Contract specifications

Every financial option is a contract between the two counterparties with the terms of the option specified in a term sheet. Option contracts may be quite complicated; however, at minimum, they usually contain the following specifications:[4]

- whether the option holder has the right to buy (a call option) or the right to sell (a put option)

- the quantity and class of the underlying asset(s) (e.g., 100 shares of XYZ Co. B stock)

- the strike price, also known as the exercise price, which is the price at which the underlying transaction will occur upon exercise

- the expiration date, or expiry, which is the last date the option can be exercised

- the settlement terms, for instance whether the writer must deliver the actual asset on exercise, or may simply tender the equivalent cash amount

- the terms by which the option is quoted in the market to convert the quoted price into the actual premium – the total amount paid by the holder to the writer

Types

The Options can be classified into following types:

Exchange-traded options

- Exchange-traded options (also called "listed options") are a class of exchange-traded derivatives. Exchange traded options have standardized contracts, and are settled through a clearing house with fulfillment guaranteed by the credit of the exchange. Since the contracts are standardized, accurate pricing models are often available. Exchange-traded options include:[5][6]

- stock options,

- commodity options,

- bond options and other interest rate options

- stock market index options or, simply, index options and

- options on futures contracts

- callable bull/bear contract

Over-the-counter

- Over-the-counter options (OTC options, also called "dealer options") are traded between two private parties, and are not listed on an exchange. The terms of an OTC option are unrestricted and may be individually tailored to meet any business need. In general, at least one of the counterparties to an OTC option is a well-capitalized institution. Option types commonly traded over the counter include:

Other option types

Another important class of options, particularly in the U.S., are employee stock options, which are awarded by a company to their employees as a form of incentive compensation. Other types of options exist in many financial contracts, for example real estate options are often used to assemble large parcels of land, and prepayment options are usually included in mortgage loans. However, many of the valuation and risk management principles apply across all financial options.

Option styles

Naming conventions are used to help identify properties common to many different types of options. These include:

- European option – an option that may only be exercised on expiration.

- American option – an option that may be exercised on any trading day on or before expiry.

- Bermudan option – an option that may be exercised only on specified dates on or before expiration.

- Barrier option – any option with the general characteristic that the underlying security's price must pass a certain level or "barrier" before it can be exercised.

- Exotic option – any of a broad category of options that may include complex financial structures.[7]

- Vanilla option – any option that is not exotic.

Valuation models

The value of an option can be estimated using a variety of quantitative techniques based on the concept of risk neutral pricing and using stochastic calculus. The most basic model is the Black–Scholes model. More sophisticated models are used to model the volatility smile. These models are implemented using a variety of numerical techniques.[8] In general, standard option valuation models depend on the following factors:

- The current market price of the underlying security,

- the strike price of the option, particularly in relation to the current market price of the underlying (in the money vs. out of the money),

- the cost of holding a position in the underlying security, including interest and dividends,

- the time to expiration together with any restrictions on when exercise may occur, and

- an estimate of the future volatility of the underlying security's price over the life of the option.

More advanced models can require additional factors, such as an estimate of how volatility changes over time and for various underlying price levels, or the dynamics of stochastic interest rates.

The following are some of the principal valuation techniques used in practice to evaluate option contracts.

Black–Scholes

Following early work by Louis Bachelier and later work by Edward O. Thorp, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes made a major breakthrough by deriving a differential equation that must be satisfied by the price of any derivative dependent on a non-dividend-paying stock. By employing the technique of constructing a risk neutral portfolio that replicates the returns of holding an option, Black and Scholes produced a closed-form solution for a European option's theoretical price.[9] At the same time, the model generates hedge parameters necessary for effective risk management of option holdings. While the ideas behind the Black–Scholes model were ground-breaking and eventually led to Scholes and Merton receiving the Swedish Central Bank's associated Prize for Achievement in Economics (a.k.a., the Nobel Prize in Economics),[10] the application of the model in actual options trading is clumsy because of the assumptions of continuous (or no) dividend payment, constant volatility, and a constant interest rate. Nevertheless, the Black–Scholes model is still one of the most important methods and foundations for the existing financial market in which the result is within the reasonable range.[11]

Stochastic volatility models

Since the market crash of 1987, it has been observed that market implied volatility for options of lower strike prices are typically higher than for higher strike prices, suggesting that volatility is stochastic, varying both for time and for the price level of the underlying security. Stochastic volatility models have been developed including one developed by S.L. Heston.[12] One principal advantage of the Heston model is that it can be solved in closed-form, while other stochastic volatility models require complex numerical methods.[12]

Model implementation

Once a valuation model has been chosen, there are a number of different techniques used to take the mathematical models to implement the models.

Analytic techniques

In some cases, one can take the mathematical model and using analytical methods develop closed form solutions such as Black–Scholes and the Black model. The resulting solutions are readily computable, as are their "Greeks".

Binomial tree pricing model

Closely following the derivation of Black and Scholes, John Cox, Stephen Ross and Mark Rubinstein developed the original version of the binomial options pricing model.[13] [14] It models the dynamics of the option's theoretical value for discrete time intervals over the option's life. The model starts with a binomial tree of discrete future possible underlying stock prices. By constructing a riskless portfolio of an option and stock (as in the Black–Scholes model) a simple formula can be used to find the option price at each node in the tree. This value can approximate the theoretical value produced by Black Scholes, to the desired degree of precision. However, the binomial model is considered more accurate than Black–Scholes because it is more flexible; e.g., discrete future dividend payments can be modeled correctly at the proper forward time steps, and American options can be modeled as well as European ones. Binomial models are widely used by professional option traders. The Trinomial tree is a similar model, allowing for an up, down or stable path; although considered more accurate, particularly when fewer time-steps are modelled, it is less commonly used as its implementation is more complex.

Monte Carlo models

For many classes of options, traditional valuation techniques are intractable because of the complexity of the instrument. In these cases, a Monte Carlo approach may often be useful. Rather than attempt to solve the differential equations of motion that describe the option's value in relation to the underlying security's price, a Monte Carlo model uses simulation to generate random price paths of the underlying asset, each of which results in a payoff for the option. The average of these payoffs can be discounted to yield an expectation value for the option.[15] Note though, that despite its flexibility, using simulation for American styled options is somewhat more complex than for lattice based models.

Finite difference models

The equations used to model the option are often expressed as partial differential equations (see for example Black–Scholes PDE). Once expressed in this form, a finite difference model can be derived, and the valuation obtained. A number of implementations of finite difference methods exist for option valuation, including: explicit finite difference, implicit finite difference and the Crank-Nicholson method. A trinomial tree option pricing model can be shown to be a simplified application of the explicit finite difference method. Although the finite difference approach is mathematically sophisticated, it is particularly useful where changes are assumed over time in model inputs – for example dividend yield, risk free rate, or volatility, or some combination of these – that are not tractable in closed form.

Other models

Other numerical implementations which have been used to value options include finite element methods. Additionally, various short rate models have been developed for the valuation of interest rate derivatives, bond options and swaptions. These, similarly, allow for closed-form, lattice-based, and simulation-based modelling, with corresponding advantages and considerations.

Risks

As with all securities, trading options entails the risk of the option's value changing over time. However, unlike traditional securities, the return from holding an option varies non-linearly with the value of the underlying and other factors. Therefore, the risks associated with holding options are more complicated to understand and predict.

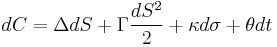

In general, the change in the value of an option can be derived from Ito's lemma as:

where the Greeks  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are the standard hedge parameters calculated from an option valuation model, such as Black–Scholes, and

are the standard hedge parameters calculated from an option valuation model, such as Black–Scholes, and  ,

,  and

and  are unit changes in the underlying's price, the underlying's volatility and time, respectively.

are unit changes in the underlying's price, the underlying's volatility and time, respectively.

Thus, at any point in time, one can estimate the risk inherent in holding an option by calculating its hedge parameters and then estimating the expected change in the model inputs,  ,

,  and

and  , provided the changes in these values are small. This technique can be used effectively to understand and manage the risks associated with standard options. For instance, by offsetting a holding in an option with the quantity

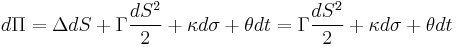

, provided the changes in these values are small. This technique can be used effectively to understand and manage the risks associated with standard options. For instance, by offsetting a holding in an option with the quantity  of shares in the underlying, a trader can form a delta neutral portfolio that is hedged from loss for small changes in the underlying's price. The corresponding price sensitivity formula for this portfolio

of shares in the underlying, a trader can form a delta neutral portfolio that is hedged from loss for small changes in the underlying's price. The corresponding price sensitivity formula for this portfolio  is:

is:

Example

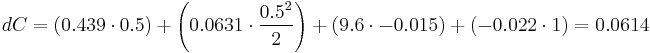

A call option expiring in 99 days on 100 shares of XYZ stock is struck at $50, with XYZ currently trading at $48. With future realized volatility over the life of the option estimated at 25%, the theoretical value of the option is $1.89. The hedge parameters  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  are (0.439, 0.0631, 9.6, and −0.022), respectively. Assume that on the following day, XYZ stock rises to $48.5 and volatility falls to 23.5%. We can calculate the estimated value of the call option by applying the hedge parameters to the new model inputs as:

are (0.439, 0.0631, 9.6, and −0.022), respectively. Assume that on the following day, XYZ stock rises to $48.5 and volatility falls to 23.5%. We can calculate the estimated value of the call option by applying the hedge parameters to the new model inputs as:

Under this scenario, the value of the option increases by $0.0614 to $1.9514, realizing a profit of $6.14. Note that for a delta neutral portfolio, where by the trader had also sold 44 shares of XYZ stock as a hedge, the net loss under the same scenario would be ($15.86).

Pin risk

A special situation called pin risk can arise when the underlying closes at or very close to the option's strike value on the last day the option is traded prior to expiration. The option writer (seller) may not know with certainty whether or not the option will actually be exercised or be allowed to expire worthless. Therefore, the option writer may end up with a large, unwanted residual position in the underlying when the markets open on the next trading day after expiration, regardless of their best efforts to avoid such a residual.

Counterparty risk

A further, often ignored, risk in derivatives such as options is counterparty risk. In an option contract this risk is that the seller won't sell or buy the underlying asset as agreed. The risk can be minimized by using a financially strong intermediary able to make good on the trade, but in a major panic or crash the number of defaults can overwhelm even the strongest intermediaries.

Trading

The most common way to trade options is via standardized options contracts that are listed by various futures and options exchanges. [16] Listings and prices are tracked and can be looked up by ticker symbol. By publishing continuous, live markets for option prices, an exchange enables independent parties to engage in price discovery and execute transactions. As an intermediary to both sides of the transaction, the benefits the exchange provides to the transaction include:

- fulfillment of the contract is backed by the credit of the exchange, which typically has the highest rating (AAA),

- counterparties remain anonymous,

- enforcement of market regulation to ensure fairness and transparency, and

- maintenance of orderly markets, especially during fast trading conditions.

Over-the-counter options contracts are not traded on exchanges, but instead between two independent parties. Ordinarily, at least one of the counterparties is a well-capitalized institution. By avoiding an exchange, users of OTC options can narrowly tailor the terms of the option contract to suit individual business requirements. In addition, OTC option transactions generally do not need to be advertised to the market and face little or no regulatory requirements. However, OTC counterparties must establish credit lines with each other, and conform to each others clearing and settlement procedures.

With few exceptions,[17] there are no secondary markets for employee stock options. These must either be exercised by the original grantee or allowed to expire worthless.

The basic trades of traded stock options (American style)

These trades are described from the point of view of a speculator. If they are combined with other positions, they can also be used in hedging. An option contract in US markets usually represents 100 shares of the underlying security.[18]

Long call

A trader who believes that a stock's price will increase might buy the right to purchase the stock (a call option) rather than just purchase the stock itself. He would have no obligation to buy the stock, only the right to do so until the expiration date. If the stock price at expiration is above the exercise price by more than the premium (price) paid, he will profit. If the stock price at expiration is lower than the exercise price, he will let the call contract expire worthless, and only lose the amount of the premium. A trader might buy the option instead of shares, because for the same amount of money, he can control (leverage) a much larger number of shares.

Long put

A trader who believes that a stock's price will decrease can buy the right to sell the stock at a fixed price (a put option). He will be under no obligation to sell the stock, but has the right to do so until the expiration date. If the stock price at expiration is below the exercise price by more than the premium paid, he will profit. If the stock price at expiration is above the exercise price, he will let the put contract expire worthless and only lose the premium paid.

Short call

A trader who believes that a stock price will decrease can sell the stock short or instead sell, or "write," a call. The trader selling a call has an obligation to sell the stock to the call buyer at the buyer's option. If the stock price decreases, the short call position will make a profit in the amount of the premium. If the stock price increases over the exercise price by more than the amount of the premium, the short will lose money, with the potential loss unlimited.

Short put

A trader who believes that a stock price will increase can buy the stock or instead sell, or "write", a put. The trader selling a put has an obligation to buy the stock from the put buyer at the put buyer's option. If the stock price at expiration is above the exercise price, the short put position will make a profit in the amount of the premium. If the stock price at expiration is below the exercise price by more than the amount of the premium, the trader will lose money, with the potential loss being up to the full value of the stock. A benchmark index for the performance of a cash-secured short put option position is the CBOE S&P 500 PutWrite Index (ticker PUT).

Option strategies

Combining any of the four basic kinds of option trades (possibly with different exercise prices and maturities) and the two basic kinds of stock trades (long and short) allows a variety of options strategies. Simple strategies usually combine only a few trades, while more complicated strategies can combine several.

Strategies are often used to engineer a particular risk profile to movements in the underlying security. For example, buying a butterfly spread (long one X1 call, short two X2 calls, and long one X3 call) allows a trader to profit if the stock price on the expiration date is near the middle exercise price, X2, and does not expose the trader to a large loss.

An Iron condor is a strategy that is similar to a butterfly spread, but with different strikes for the short options – offering a larger likelihood of profit but with a lower net credit compared to the butterfly spread.

Selling a straddle (selling both a put and a call at the same exercise price) would give a trader a greater profit than a butterfly if the final stock price is near the exercise price, but might result in a large loss.

Similar to the straddle is the strangle which is also constructed by a call and a put, but whose strikes are different, reducing the net debit of the trade, but also reducing the risk of loss in the trade.

One well-known strategy is the covered call, in which a trader buys a stock (or holds a previously-purchased long stock position), and sells a call. If the stock price rises above the exercise price, the call will be exercised and the trader will get a fixed profit. If the stock price falls, the call will not be exercised, and any loss incurred to the trader will be partially offset by the premium received from selling the call. Overall, the payoffs match the payoffs from selling a put. This relationship is known as put-call parity and offers insights for financial theory. A benchmark index for the performance of a buy-write strategy is the CBOE S&P 500 BuyWrite Index (ticker symbol BXM).

Historical uses of options

Contracts similar to options are believed to have been used since ancient times. In the real estate market, call options have long been used to assemble large parcels of land from separate owners; e.g., a developer pays for the right to buy several adjacent plots, but is not obligated to buy these plots and might not unless he can buy all the plots in the entire parcel. Film or theatrical producers often buy the right — but not the obligation — to dramatize a specific book or script. Lines of credit give the potential borrower the right — but not the obligation — to borrow within a specified time period.

Many choices, or embedded options, have traditionally been included in bond contracts. For example many bonds are convertible into common stock at the buyer's option, or may be called (bought back) at specified prices at the issuer's option. Mortgage borrowers have long had the option to repay the loan early, which corresponds to a callable bond option.

In London, puts and "refusals" (calls) first became well-known trading instruments in the 1690s during the reign of William and Mary.[19]

Privileges were options sold over the counter in nineteenth century America, with both puts and calls on shares offered by specialized dealers. Their exercise price was fixed at a rounded-off market price on the day or week that the option was bought, and the expiry date was generally three months after purchase. They were not traded in secondary markets.

Supposedly the first option buyer in the world was the ancient Greek mathematician and philosopher Thales of Miletus. On a certain occasion, it was predicted that the season's olive harvest would be larger than usual, and during the off-season he acquired the right to use a number of olive presses the following spring. When spring came and the olive harvest was larger than expected he exercised his options and then rented the presses out at much higher price than he paid for his 'option'.[20][21]

See also

- American Stock Exchange

- Chicago Board Options Exchange

- Eurex

- Euronext.liffe

- International Securities Exchange

- NYSE Arca

- Philadelphia Stock Exchange

- LEAPS (finance)

- Real options analysis

- PnL Explained

References

- ^ a b Pascucci, Andrea. Pde and Martingale Methods in Option Pricing. Berlin: Springer, 2011.

- ^ Brealey, Richard A.; Myers, Stewart (2003), Principles of Corporate Finance (7th ed.), McGraw-Hill, Chapter 20

- ^ Hull, John C. (2005), Options, Futures and Other Derivatives (excerpt by Fan Zhang) (6th ed.), Pg 6: Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0131499084, http://fan.zhang.gl/ecref/options

- ^ (PDF) Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options, Options Clearing Corporation, http://www.theocc.com/publications/risks/riskstoc.pdf, retrieved 2007-06-21

- ^ Trade CME Products, Chicago Mercantile Exchange, http://www.cme.com/trading/, retrieved 2007-06-21

- ^ ISE Traded Products, International Securities Exchange, archived from the original on 2007-05-11, http://web.archive.org/web/20070511003741/http://www.iseoptions.com/products_traded.aspx, retrieved 2007-06-21

- ^ Fabozzi, Frank J. (2002), The Handbook of Financial Instruments (Page. 471) (1st ed.), New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons Inc, ISBN 0-471-22092-2

- ^ Reilly, Frank K.; Brown, Keith C. (2003), Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management (7th ed.), Thomson Southwestern, Chapter 23

- ^ Black, Fischer and Myron S. Scholes. "The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities," Journal of Political Economy, 81 (3), 637–654 (1973).

- ^ Das, Satyajit (2006), Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and unknowns in the dazzling world of derivatives (6th ed.), Prentice-Hall, Chapter 1 'Financial WMDs – derivatives demagoguery,' p.22, ISBN 978-0-273-70474-4

- ^ Hull, John C. (2005), Options, Futures and Other Derivatives (6th ed.), Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0131499084

- ^ a b Jim Gatheral (2006), The Volatility Surface, A Practitioner's Guide, Wiley Finance, ISBN 978-0471792512, http://www.amazon.com/Volatility-Surface-Practitioners-Guide-Finance/dp/0471792519

- ^ Cox JC, Ross SA and Rubinstein M. 1979. Options pricing: a simplified approach, Journal of Financial Economics, 7:229–263.[1]

- ^ Cox, John C.; Rubinstein, Mark (1985), Options Markets, Prentice-Hall, Chapter 5

- ^ Crack, Timothy Falcon (2004), Basic Black–Scholes: Option Pricing and Trading (1st ed.), pp. 91–102, ISBN 0-9700552-2-6, http://www.BasicBlackScholes.com/

- ^ Harris, Larry (2003), Trading and Exchanges, Oxford University Press, pp.26–27

- ^ Elinor Mills (2006-12-12), Google unveils unorthodox stock option auction, CNet, http://news.com.com/Google+unveils+unorthodox+stock+option+auction/2100-1030_3-6143227.html, retrieved 2007-06-19

- ^ invest-faq or Law & Valuation for typical size of option contract

- ^ Smith, B. Mark (2003), History of the Global Stock Market from Ancient Rome to Silicon Valley, University of Chicago Press, pp. 20, ISBN 0-226-76404-4

- ^ Mattias Sander. Bondesson's Representation of the Variance Gamma Model and Monte Carlo Option Pricing. Lunds Tekniska Högskola 2008

- ^ Aristotle. Politics.

Further reading

- Fischer Black and Myron S. Scholes. "The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities," Journal of Political Economy, 81 (3), 637–654 (1973).

- Feldman, Barry and Dhuv Roy. "Passive Options-Based Investment Strategies: The Case of the CBOE S&P 500 BuyWrite Index." The Journal of Investing, (Summer 2005).

- Kleinert, Hagen, Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets, 4th edition, World Scientific (Singapore, 2004); Paperback ISBN 981-238-107-4 (also available online: PDF-files)

- Hill, Joanne, Venkatesh Balasubramanian, Krag (Buzz) Gregory, and Ingrid Tierens. "Finding Alpha via Covered Index Writing." Financial Analysts Journal. (Sept.-Oct. 2006). pp. 29–46.

- Moran, Matthew. “Risk-adjusted Performance for Derivatives-based Indexes – Tools to Help Stabilize Returns.” The Journal of Indexes. (Fourth Quarter, 2002) pp. 34 – 40.

- Reilly, Frank and Keith C. Brown, Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management, 7th edition, Thompson Southwestern, 2003, pp. 994–5.

- Schneeweis, Thomas, and Richard Spurgin. "The Benefits of Index Option-Based Strategies for Institutional Portfolios" The Journal of Alternative Investments, (Spring 2001), pp. 44 – 52.

- Whaley, Robert. "Risk and Return of the CBOE BuyWrite Monthly Index" The Journal of Derivatives, (Winter 2002), pp. 35 – 42.

- Bloss, Michael; Ernst, Dietmar; Häcker Joachim (2008): Derivatives – An authoritative guide to derivatives for financial intermediaries and investors Oldenbourg Verlag München ISBN 978-3-486-58632-9

- Espen Gaarder Haug & Nassim Nicholas Taleb (2008): "Why We Have Never Used the Black–Scholes–Merton Option Pricing Formula"

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||